Crypto primitives

Technologies and behaviors that have emerged in crypto, and the real world use cases that might benefit from them

I’ve spent years thinking passively in the background what use cases there are for crypto and decentralized finance. I struggle a lot with the narrative around the benefits of permissionless, decentralized, money analogues because I don’t yet believe these are necessarily valuable in and of themselves. For example, it's very likely that most people who don’t trust their bank simply want a place to store their money that they can trust, not “decentralization”. Decentralization might be one tool to build a trustworthy system, but a system is not trustworthy simply because it's decentralized. I think these features will have to unlock novel, useful experiences to be truly valuable.

I’ve arrived at a collection of things I can best describe as primitives - simple elements that don’t necessarily represent a use case, but can be used alone or in combination with others to create real world utility. Some of these are technically interesting (as in the underlying technology is interesting), but some are interesting because they’ve demonstrated that a user will actually engage in a new behavior that would have struggled to gain adoption without the “number go up” virality (cant think of a better way to to describe this) of something like crypto. Main caveat - I’m not remotely a crypto expert or practitioner, I just like to think about experiences you can create that are original and useful. For the purposes of this I’m describing crypto as everything under crypto/web3/defi because for most people not in the space, they're not distinguishable. In addition, for each I’m describing who will use it, how, why, and what benefit they receive from using crypto this way, and why its better than what they currently use.

Not Digital gold

One way to think about how gold is valued is

-

its utility value (functionality that requires gold to exist, like certain electronics and other industrial applications), +

-

It’s aesthetic value (reasons people buy gold that aren't strictly functional or accomplishing a specifc task, eg jewelry), +

-

It’s belief value (eg people believe if they show up somewhere with gold, other people will trade goods with them and accept gold in exchange, because that has been the case for thousands of years)

This means that even if the belief value fell to zero (ie if everyone stopped believing they could exchange gold for goods and services), gold would still have some residual value equal to what people would pay for jewelry and for gold’s use in industrial applications. Thus far, bitcoin is mostly belief value (I say mostly because it also functions kind of like the reserve currency of crypto which is a kind of utility value, but the real commercial activity denominated in crypto is somewhat sparse so it’s hard to say that this has actual utility. If all the rest of crypto were to go away today, the utility of being a reserve currency would be zero).

Fundamentally in order for a currency to have actual economic value, real commercial activity (eg I assemble a bunch of components with $0.90 of aggregate value into a widget and sell the widget for $1) has to be denominated in the currency, and right now basically no crypto really has any meaningful non-crypto (or real, offline world) economic activity denominated in it yet. Because of this, its value is 100% (or maybe 99%) belief value. Beliefs are super valuable! Just look at religion. But also quite fickle in a way that growing tomatoes is not. I can imagine someone saying that USDT/ADA liquidity pool is an example of real economic activity, but just because you’re earning a spread off two fake things doesn’t make it real.

As a result, it has the potential to become digital gold in the sense that it is the largest digital “asset” to emerge in the last 20 years in terms of belief value (and has kind of demonstrated how quickly belief value can accrue if the conditions are right), but it is explicitly NOT YET digital gold in the sense that the vast majority of people and institutions who actually use gold for things do not believe bitcoin is a substitute for the things they use it for, and they vote with their money, and their money is in gold. One way to measure how well bitcoin is tracking towards this objective is to compare it to the way gold is described today; as a hedge against inflation, because there is limited supply. I think the bitcoin-as-digital-gold thesis kind of relies on the idea that because bitcoin is of limited supply, ergo it is a hedge against inflation. In almost every scenario since the advent of bitcoin where there has been an opportunity for financial market participants to lean into an inflation hedge, they’ve chosen gold, and bitcoin continues to just trade like a correlated commodity. Some of this is structural; the regulatory setup for a lot of central banks, broker dealers and portfolio managers already explicitly allows them to trade and invest in gold (and have for years), but the same is not (yet) true for bitcoin (ie, maybe the portfolio manager at PIMCO actually believes bitcoin is an inflation hedge but just cant trade it because the PIMCO charter doesn’t let them). But some of it is belief - a lot of traditional financial market participants simply do not yet believe bitcoin is digital gold. This obviously can change over time, and I suspect it will as people who grew up with bitcoin just existing in the background mature into portfolio managers and central bank economists, but a) that’s a generation away and b) even then it’s not clear what other attributes are necessary to make this true.

A few really funny dimensions emerge when you think of bitcoin this way. First, transacting in bitcoin leaves a kind of infinite paper trail. Gold does not. Second, crytpo is actually far easier to steal than gold. You can hide a billion dollars worth of bitcoin in your pocket. Try doing that with gold. Third (this is probably the thing that is least understood by bitcoin proponents in western countries) money/wealth is ultimately protected by property rights. Property rights are secured by courts, contracts, and ultimately state violence (ie if I take your money in a way that a court deems is not appropriate, I can literally be thrown in jail). Nothing about cryptocurrency changes this dynamic. It might make it kind of easier to hide, or reduce the likelihood that the state knows what money you have or what you do with it, for a time, but all property is secured by violence; in stable economies, that violence mostly wielded by the state, and elsewhere, it might just be wielded by the person who wants to take your property from you. For all the comments describing crypto as permissionless, a currency that has an undeletable paper trail cannot truly be permissionless because there is always the threat that your identity gets revealed and the state shows up to enforce permission. Lastly, gold does not require electricity to be used/transacted. All crypto does. In most western countries, electricity is a given, but in lots of the world (and even in US states like CA, TX and NJ), you can’t take for granted that you will always have power. In the apocalypse scenario that lots of bitcoiners “prep” for, the odds that any cryptocurrency surpasses gold as the store of value or means of exchange remains crazy unlikely.

Stablecoins for Emerging Markets

The “digital gold” pitch for cryptocurrency (ie, that it is a hedge for inflation and its permissionless nature enables consumers to protect themselves from a wealth seizure by their local government) is far more true for stablecoins (a cryptocurrency pegged to a reserve currency like the US Dollar), than it is for bitcoin.

As a person in a country with a mismanaged currency, you might in theory want to own bitcoin at some stage for speculative purposes. However, the volatility so far makes it atrocious as a store of value, because you have no confidence about how much value will be available to you when you actually need to use it. Said another way, in emerging markets, the average citizen does not have the capital reserves needed to stomach this new asset's volatility. It makes it a very expensive and inefficient store of value in the short term. In contrast, prior to the existence of cryptocurrency, it was (and still is) fairly common for wealthy individuals in poor countries to hold foreign currency (typically USD, GBP or EUR) as a mechanism for savings. As a market maker, I used to think (and I still think) that a good heuristic for a country’s economic trajectory is where do the country’s rich put their wealth. Wherever wealth is exported (eg if the move when you get rich is to immediately buy New York or London real estate) is a signal that citizens are afraid of wealth seizure (either explicitly by taking it away, or implicitly by printing it away).

Governments hate this because it creates natural selling pressure for their home currency, but a fiat-backed stablecoin pegged to the US Dollar or Euro (with real assets under management) that is permissionless and effectively beyond the ability of the government to stop you from buying, is simply a digital asset substitute for a real use case that exists. Before stablecoins, you had to buy dollars from a bank and keep it in a bank account (which has it’s merits) but the bank could also a) just refuse to sell them to you, b) charge you a ton of fees to buy or hold it or c) be forced by the government to transact at a fake exchange rate or limit how much you could buy or own. Even in today’s environment, if you’re in the US you should try going to your local Bank of America or logging into your Chase mobile app and try to buy some euros, and it will become blindingly obvious how unsupported this is.

Basically, everyone around the world want access to a relatively stable currency that has a predictable exchange rate vs. the goods and services they purchase every day. For many people, dollars and euros are more stable than their home currency. A stablecoin backed by the dollar (or GBP, EUR, take your pick), is a permissionless way to do that. The loudest voices in crypto aren’t incented to tell you this because USDC doesn’t make them rich (maybe other than the folks behind Tether[1]). Ironically, stablecoins actually help solve the runaway hyperinflation use case, while bitcoin merely enables a user to swap hyperinflation in their home currency for volatility in crypto.

Automated Market Makers (AMMs) == Fixed Income Market Makers

In a previous life I used to trade government bonds and foreign currency as a market maker. At scale, all institutional markets need the market making function (someone who stands in and tells you at what price they’d buy or sell your inventory) because market makers enhance liquidity, and liquid markets mean more reliable pricing of securities, low transaction costs, and more. . The average person thinks of the market making function as “Wall Street” and the associated fee pool (the amount of income generated annually) is pretty large ($150bn as of 2021)[2]. Not all these fees are applicable (for example the Wall Street fee pool includes fees for things like bond placements or IPOs) from what I’m about to describe, but a large amount are.

These fees are funded essentially by spreads. The price of a particular Apple bond might be $150, but the market maker is willing to pay $149 to buy the security from you, and will sell it to you for $151. If you buy for $149 and sell for $151 over a large enough number of securities and you’re looking at real money. The spread keeps them in business, and ensures that they are around to buy your bonds when you need liquidity. Today, this function is played primarily by broker dealers such as JPMorgan and Goldman. Humans at these companies are available during market hours to make markets typically for corporate (Eg GE) or institutional (eg CalPers) buyers and sellers and get paid pretty handsomely to do so.

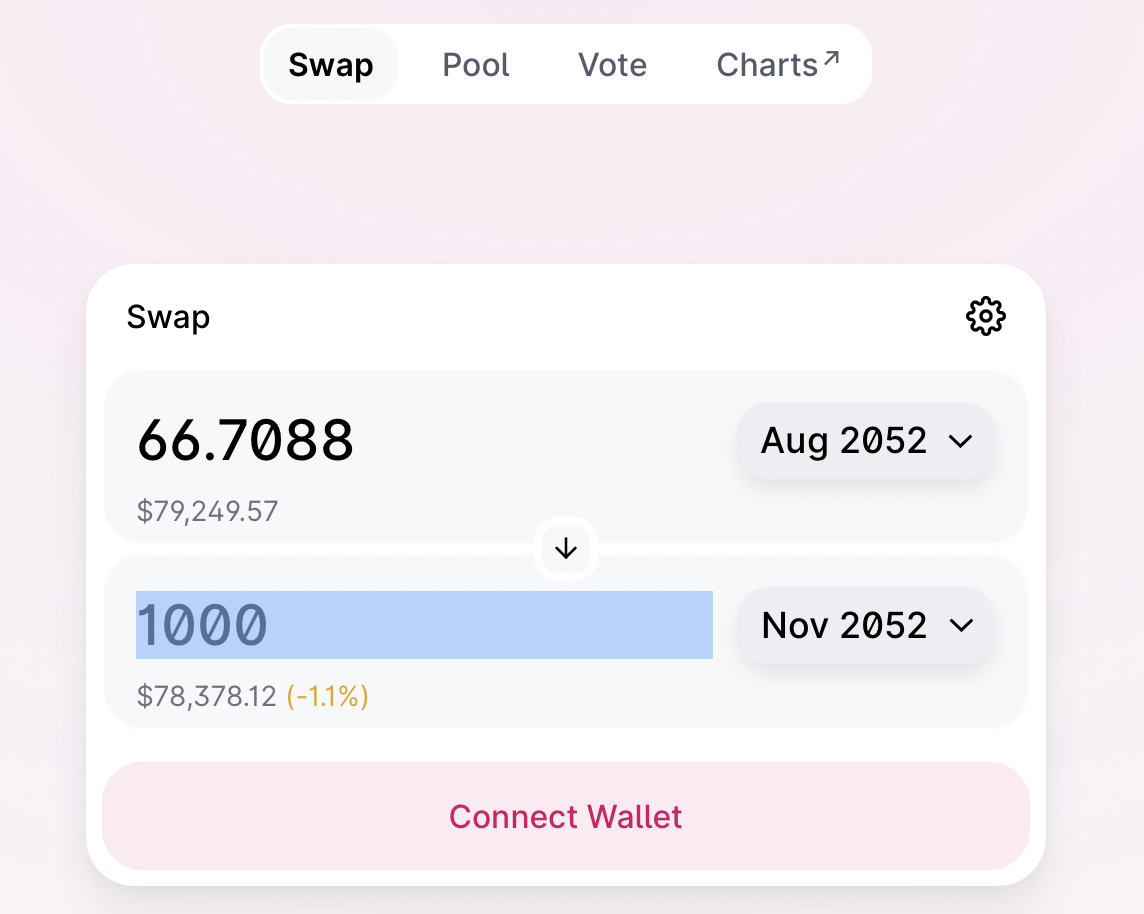

My first experience with AMM contracts was on Uniswap in 2021. I put ETH and ENS into a Uniswap V2 liquidity pool via Rainbow wallet. I consider myself a relatively sophisticated consumer of both software and money products and figuring out what a Uniswap contract was and how to use it was extremely bewildering. While this onboarding problem is solvable for consumers over time, I think the AMM concept is far more transformational for institutional securities and market liquidity, than for consumers.

AMMs create a material yield earning opportunity to denominate real economic activity on-chain. While substantially deepening the actual liquidity of a ton of markets in the process.. Here’s how it could work

-

Calpers (or insert a large institutional long term holder of treasurys) might buy $500m worth of August 2050 30y US Treasurys from the Federal Reserve. They plan to (within some range) hold these to maturity as a match against pension liabilities.

-

Calpers (or insert a large institutional long term holder of treasurys) might also buy $700m worth of November 2050 30y US Treasurys from the Federal Reserve. They also plan to (within some range) hold these to maturity.

-

Calpers might be indifferent (within some relative value range) to how much of each they own. Maybe $600m of each is acceptable. So they spin up their own liquidity pool with 500m of each issue, out of their own inventory, at 0.3% commission level on Uniswap.

-

Every time someone traded the Aug-50s in exchange for the Nov-50s, CalPers would earn a commission which they could take as a direct payout, reinvest, etc (just depends on how the smart contract is designed). You do this, and you could instantly have a relatively deep liquidity pool that rivals the centralized exchanges that currently dominate treasurys.

I no longer do this for a living, so I’ve no idea which exchange dominates, but when I was trading treasurys the dominant electronic players were centralized exchanges called Brokertec and Tradeweb. Both were initially dealer to dealer exchanges (Brokertec is now owned by CME) that started as industry consortiums where Goldman/Morgan etc all the broker dealers would pool their volume in one place to solve the cold start problem, and would be the only shareholders and market participants. This dynamic meant (at least in the early days) that large institutional players couldn’t access the exchanges, and in order to access liquidity, they would have to go to the broker dealers. Now there are good reasons to work with broker dealers - the most important being size and transparency. If you’re about to move a really large block of some security, having everyone know about it beforehand (or in real time) could actually demolish your return profile, as they will front run the crap out of you. But, you’re not moving large sizes every day, and as an institutional money manager, you are graded on returns, and if there was a new vector to earn yield, it would be almost an abdication of your fiduciary duty to ignore it. The best part is, even tiny money managers can solve the cold start problem by themselves, and create insane amounts of liquidity by themselves. For reference, the single deepest liquidity pool on Uniswap as of this writing was the 0.01% DAI/USDC LP, with ~$700m in total value locked[3].

In fixed income, $680m is a really small trade. For an idea of how large these markets are, $833b in notional value is traded on Tradeweb each day as of May 2022. This means that even at the height of the crypto craze of 2021, the volume on a single centralized fixed income exchange traded every 4 days was greater than the entire market capitalization of every cryptocurrency ever created. For Brokertec, that number is $700Bn traded each day (as of May 2022). Even at infinitesimal commission levels, the fees up for grabs here are dramatic, and as a result, incumbent broker dealers are extremely incentivized to fight against this, because gargantuan employee bonus pools are at stake. Broker dealers initially even fought electronic trading of fixed income!

I think there are a few key reasons why this hasn’t happened yet

-

There are real regulatory hurdles around figuring out how to bring securities and commodities onchain in a systematic/non bespoke way so participants can trust that the digital asset they are acquiring maps to the real underlying security

-

DEX’s are profitable enough from the perspective of the humans building them vs. the revenue leverage created. The humans building them have generated an insane amount of value for themselves and for participants relative, to what they were doing only a couple of years ago

-

Broker dealers hate it, and won’t try it

-

Traditional equity/commodity/fixed income market participants literally do not spend their waking hours thinking about crypto and defi for the most part (I mean I’ve been muddling around in crypto for years and i did not understand what an AMM was until 6 months ago)

-

Most folks building in crypto do not actually come from the traditional financial markets, and as a result are just not really aware of the relative sizes and values. The top 10 largest asset managers each have more assets under management than the entire market cap of crypto.

The main reason I think this will happen eventually, is that fiscal and monetary authorities (the US Treasury & the Federal Reserve) really do want markets to be liquid and transaction costs to be low, because it reduces rates the government has to pay to borrow, and helps cement the US position as a reserve currency[4]. It also solves a second order liquidity problem - the greatest liquidity in treasury markets are in the most recently issued securities; everything that’s considered off-the-run[5] (basically old issuance) just doesn’t trade as well. Bringing persistent, deep liquidity to off the run treasuries will mean more points along the yield curve are explicitly priced (based on recently trading pairs) rather than priced on relative value (which often happens today). I think the application of AMMs to fixed income markets is where crypto/defi has some of the greatest potential because the TAM is so large - greater yield for long term securities holders (which benefits institutional investors), more liquidity for fixed income securities (which benefits monetary and fiscal authorities via more stable markets) and lower spreads, transaction costs, and borrowing costs via a higher precision yield curve (which will benefit both corporate and government borrowers). In the relative value context, impermanent loss is a feature more than a bug - at some relative valuation differential between two securities, as an institutional holder, you'd actually prefer to hold one over the other. One company I’ve heard of working on a variant of tokenization of fixed income securities is https://digitalasset.com/. Not sure how far along they are or whether they're pursuing the AMM vector, or something else.

AMM Contracts for Currency trading

Most currency pairs are anchored first by a deep commercial need for the two currencies to trade against each other. For example, there’s lots of fundamental commercial activity between the US and Mexico, because they share a border and lots of firms on both sides of it trade with each other, buying food, manufactured goods, paying wages, sending remittances, and so forth. Tons of financial firms exist around the USD/MXN pair, and there’s lots of fees and deep liquidity servicing corporate and consumer needs around it.

In contrast, if two countries don’t have lots of direct commercial activity between them (eg like Botswana vs. Brazil), you get an exotic pair that is highly illiquid. In the occasion where a Brazilian firm gets paid in Botswanan Pulas and needs Brazilian Reais, they are probably going to pay a lot of fees to go Pula > EUR > Reais (or some other intermediate currency, paying rich spreads on each leg).

There’s an opportunity here that is similar to the treasury example above. The main friction will be that governments want control, but governments have an interest in liquid currency markets where spreads are fairly tight, because it reduces the odds that disorderly events happen and create chaos for consumers, importers, exporters and other users of the currency.

Here, I think there’s an institutional opportunity as with bonds, but there’s also an opportunity for corporates and individuals who have assets denominated in both currencies to essentially earn yields off their assets (think of the AMM example for bonds, except swap out Calpers with a massive multinational like Apple). Again, currency exchange is a fundamental economic activity, it already exists today, and the users of both currencies already transact and convert in their daily lives, and already have solid reasons to have balances in both currencies. The AMM contract simply opens an additional yield vector for retail and corporate users, anchored by institutions/governments. The currency fee pool is traditionally only open to banking market makers. If you want to have a laugh, go to your bank and ask them if you can hold half your funds in a foreign currency and earn spreads off trades using your funds as working capital. I bet you can’t even find the human at the bank who handles that activity.

On an L1 chain with low transaction fees, you can even support daily fee payouts (what a lot of NFT communities call “utility”) which can enable daily compounding APR structures similar to what credit card issuers get. These payouts could be in your home currency, and thus would be useful to you right away, with no need to do yet another currency conversion. This might seem trivial, but it’s kind of crazy that the default unsecured credit instrument most consumers use has daily compound interest against them, but there is not a single consumer investment instrument with the same compound interest framework working in their favor.

Both AMM use cases require some legal infrastructure to work and give all participants confidence that the digital asset they are holding actually maps to the real rights and obligations of the real security in the real world (eg you wanna know that what you’re paying real dollars for on uniswap is the real US Treasury.)

Similar to the AMM for fixed income use case, I think the actual main reason these institutional capital markets haven’t gone this way yet is because they require a ton of tribal knowledge and relationships and meaningful regulatory overhead, and to date, the people who have been building in crypto and tend to be loudest, have minimal overlap with people who understand equity, currency, and fixed income market structure and move around large volumes of securities for a living. I think these AMM use cases are most interesting because they are literally better for a population of users (people and corporates that hold balances in multiple currencies, that are looking to manage their treasury) than what exists today.

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) 🤝 Marketplaces

I think of the DAO concept as a new organizational technology that is uniquely suited to the internet[6]. A rough way to think about a DAO is an organization where the agreements are explicitly encoded in smart contracts rather than paper contracts (and as a result you can have lots of parties to the contracts and have those parties evolve and change over time with relatively low friction and transaction costs). This is not necessarily better than C-Corps, LLCs etc for everything, but creates some unique opportunities for specific types of entities where there might be many (thousands? millions) of parties to the agreement, with varying levels of interest and investment, and varying levels of participation. One such entity is a marketplace. One of the most frequent knocks on DAOs as they exist today (that resonates with me) is that the concept of decentralized/distributed decision making leads to worse outcomes on average. I think this is because in any organization that is trying to grow fast and has existential decisions to make, decision making speed is critical, and decentralized decision making/voting will simply never be faster. It’s like the worst aspects of consensus decision making - think of all the times you’ve had to come to consensus as a group, in almost any context, and then 1000x the number of people you need to get to agree. Anytime a decision needs to be fast, centralized decision making is just plain better.

I expect a type of organization to emerge that blends DAO scale with more traditional corporate characteristics.

-

Centralized decision making where it needs to be fast

-

Decentralized ownership & governance where it can be slow/more deliberate

The example I can think of is developing online marketplaces that are owned by the participants by default; eg Upwork but participants get some financial benefit for the network growing larger. This isn’t that crazy - Square, Uber, and Airbnb all created programs to enable participants (drivers in Uber’s case, hosts in Airbnbs case and merchants in Square’s case) to buy shares in their respective IPOs. This isn’t materially different, it’s just enabling this to happen much earlier in the company’s development.

This brings a few things to mind. First, it’s not clear if participant ownership makes a marketplace better (I think there’s something here, but I haven’t seen it done well yet so I don’t have good examples to learn from). It might make a marketplace fairer, or feel more equitable somehow - and I think this is what drove Square/Airbnb/Uber to support those programs, but all those programs were fairly marginal both from a retention and a capitalization perspective for those companies. This might also be because these companies were all household names by the time they went public, so there wasn’t much leverage to gain anyway. One possibility is that more distributed ownership might in the long run reduce fraud if participants are incentivized to keep the marketplace healthy. Another is that distributed ownership might create better retention of market participants who might otherwise use a competitive marketplace. From what I can tell though, distributed ownership doesn’t make the product better or more efficient to run in any way I can discern. In every case I’ve seen or been a part of, building a good product requires a metric ton of iteration, optimizations, context, and individuals or teams willing to make non-consensus decisions that are only obvious in hindsight. Decentralized decision making essentially makes ALL these things harder to do, thus standing in the way of a marketplace product being better. I think it’s more likely that what will happen is someone will build a marketplace that is better than the incumbents, and they will happen to have built it with a DAO ownership structure. I’ve seen one example of this - Braintrust (https://www.usebraintrust.com). Haven’t used it yet, but planning to.

DAO 🤝 Public Goods

DAOs (or massively distributed ownership with realtime voting) also seem like an alternative model for public goods, in that they can make it cheap/easy for the public to directly engage in, manage and govern public goods without an intermediary. Public goods governance doesn’t typically require rapid decision making, and tends towards consensus driven decisions anyway, and generally aren’t growing fast so centralized decision making at the governing level isn’t that advantageous. In fact, natively enabling real time voting structures from the inception of such an enterprise might result in faster decision making and greater participation than public goods have historically had (as they typically have several layers of delegation from the public to the government)

This doesn’t obviate the need for governments, but in a time when trust in institutions have started to fail, its not crazy that a new model that blends some dimensions of government and some dimensions of private organizations in which digital governance (ie voting mediated primarily by software not by offline processes) can emerge. And governments do lots of things at different scales - it would probably never make sense to govern a military entity in a decentralized way, but the same is not true for governing a national, state, or municipal park.

The best examples I’ve seen of this are CityDAO and ConstitutionDAO. You might take offense that “cryptobros want to buy the constitution” but a) it’s mechanistically quite possible, so it will probably happen one day and b) there’s almost no one who would tell you that most public goods are well managed today or most institutions are operating in the way their constituents desire. As with most of these use cases, this will require some way to bring these offline assets onchain, a local management team to handle day to day business, etc.

Central Bank Digital Currencies

The signal to me that Facebook Diem/Novi was a tractable idea, is how fast every government in the world moved to kill it once it was announced. The governments of the world didn’t even move in such a coorddinated way against COVID-19, which continues to murder millions of people every year. Diem had a couple of attributes that many coins/tokens today did not;

-

an entity that could instantly distribute it to more humans on earth than any currency in existence today - it was able to arrive at mass distribution without the “number go up” virality that all crypto relies on.

-

Tons of real world and digital economic activity could instantly be dominated in it (because tons of real world and digital economic activity already happens on Facebook)

-

It could actually obviate the need for currency exchange fees for counterparties that were otherwise across borders.

These attributes made it have a shot at actually becoming a kind of reserve currency (not a reserve currency as in something that every central bank holds some of, but a reserve currency as in something that most humans hold, and know that other humans will accept if they show up and provide it, the same way that is true for gold, and to a lesser extent, dollars). If they’d wanted it to be successful, they should have launched it before announcing. This would have likely gotten them in regulatory hot water, but a) they’re already there and b) it would then have become something the regulators had to deal with, rather than something they could block. The emergence and concerted regulatory action against Facebook probably caused monetary authorities around the world to learn about cryptocurrency faster than anything that came before, and in this way probably accelerated the likelihood that a central bank will soon develop it’s own digital currency (or just digitize its existing currency) onchain.

Media: NFTs for streaming

There is a problem that exists in the “creator” environment (primarily music, but exists elsewhere) that is related to the ability of artists to get compensated for the value they create, but is not related to the quality of the art itself. Thematically (and I say this as an outsider and not a musician or an industry veteran) a frequent complaint of artists is that streaming services like Spotify (which is the dominant consumption format in this era) do not pay them enough[7], and as a consequence most artists rely on a plethora of mechanisms to supplement their income, including tours, merch, and more.

One way to think of tokenization via smart contract is as low-cost securitization. Today, if you wanted to securitize a series of cash flows, you’d need to work with a structured products desk at an investment bank, and in order to make it worth their while they’d charge you a massive fee and in general the total notional value of those cashflows would need to be pretty large to make it worth their while (large as in the 10s of millions or greater in dollar value). Now, securitization is rare and regulated for a reason, because it’s complex to understand, and an easy way to lose your shirt as a consumer if you’re not paying attention.

The current examples I’ve seen for crypto solving problems in music looks roughly like - you’re selling the song. The model I think could work as it leverages the status/vanity dimensions of human nature looks like:

-

Artist releases song on streaming services (Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal) and media sites (Youtube etc)

-

The artist mints an NFT that receives all revenue derived from the release (or at a minimum, all revenue due to the artist, after labels and other parties have been paid). This NFT also has a royalty framework embedded in it so that every time the NFT changes hands, the artist continues to get paid. The wallet holding the NFT receives the revenue.

-

The artist can then either a) hold on to the NFT, or b) list it. Whether or not the NFT owns the core IP/Masters to the song is up for grabs (just not sure how much it matters). What matters is that there is a real series of cash flows that exists today, derived from economic activity in the real world that happens today, for which this NFT is the recipient, forever

-

A supporter of the artist can choose to buy the NFT and when they buy it they are receiving two things;

-

Art: an object created by the artist in the “NFT” medium

-

A security: ownership of a series of cash flows generated by the underlying music sales

-

This model has several benefits. The artist benefits up front because they can pull future earnings into today, in an atomic way (song by song, instead of a multi album deal for example). Second, the artist continues to receive royalties on future sales. For example, if the song in the future gets picked up in a commercial, which drives streaming uptake, the artist hasn’t completely lost out on the future popularity of the song. Third, by pulling the future benefits into today, the artist gets to finance either their lifestyle or other business/artistic endeavors. Fourth, fans benefit because they get to support artists they love, and they can demonstrate that love in a way that is decoupled from the core economics of the music business (it’s like patronage [8], but on a micro scale). I for example am a huge fan of Ayra Starr, and I do actually believe she’ll eventually be a huge global star that lots of people will know, and I’d like to listen to as much of her music as possible. However, I’m not in the music business, and I’m not a big time music producer. I also recognize that it’s unlikely she’ll ever tour in the place(s) I live, so I’ll never see her live. Even if she did tour and I spent $100 on a ticket, it’s mostly not going to her, it’s a point in time, that usually will occur once she’s popular enough to have a fan base deep enough in my geo to make it economically worthwhile, and it far undervalues the consumer surplus she creates for fans (as a heavy music consumer, the value music creates in my life is far greater than a $10 Spotify subscription). My ability to support artists I like is literally limited to a) buying an album or b) buying merch. Even if I wanted to support an artist to the tune of $200, it’s almost impossible. Buying her album on Apple Music grosses her $14.99. Maybe I buy $100 of merch (if the artist happens to be selling any). Even in all those cases, there’s no incentive alignment - it’s not like I’m going to use the 3 tshirts I happen to buy for $100.

The point I’m trying to make here is, there’s a cap on how fans can support their favorite artists, relative to how much they’d like to. That cap is both structural, in that there are limited avenues and lots of leakage in each one, and opaque, in that you always get the feeling that your favored artist is getting a minimal proportion of your support. In addition, there’s no incentive alignment; as an early supporter of an artist, at least some part of why you’d do something like this is to be proven right when the artist does prove to be huge.

I don’t think of this as an alternative financing model for music, just a supplementary one. The music industry has a pretty sophisticated approach to ownership and intellectual property, and a) I don’t know enough about it to tell if it needs to be replaced and b) there are probably very good reasons for it to exist the way it does. What is different now, is that with the rise of streaming, there are now well defined cash flows, already encoded in software, that can be securitised, and NFTs can be a new, lower cost, more mass market, securitization technology that lowers barriers to securitizing smaller pools of cash flows. My guess is similar dynamics to music exist in podcasts, ebooks, audiobooks, streaming etc.

As an artist, you’d do this because it pulls in earnings earlier, in lumpier amounts that reduce your working capital needs, and it rewards your early supporters. As a fan, you do this because you want to see your favorite artists win, and there’s not really another way to support them in an outsize way.

The crypto petri dish

One thing crypto has done so far is been a testbed for some ideas that institutional capture has made impossible to justify. This is captured well by this HN comment and this tweet:

Cryptocurrency, as always, attempting to speedrun every crisis that traditional finance has ever had.

— Patrick McKenzie (@patio11) January 14, 2021

This one, though, this would (if it comes to pass) be such an elegant, beautiful bomb that I'm sort of in awe the system is robust enough to cause it to happen.

The downside is, crypto practitioners are discovering in real time the value of property rights, laws, financial dispute mechanisms, orderly liquidation rules and more. Along the way, these experiments are costing real people real money. The upside is these experiments have revealed some tools the financial system has been slow to try. From what I can tell, the benefits a lot of crypto proponents tout are actually features (things like the decentralization, ownership, permissionless, pseudonymous etc) and the actual benefits are more interesting financial tools and some derivative constructs, primarily for institutions (and mostly not yet for retail). In this way you could almost think of crypto as a “testnet” for financial services broadly. It might also eventually become the mainnet for some use cases, but that will only happen as practitioners discover use cases at which crypto outperforms the existing tools that have developed over thousands of years.

Notes

[1]The legitimacy and stability of Tether is persistently in question (rightly so): https://www.kalzumeus.com/2022/05/20/tether-required-recapitalization/

[3] https://info.uniswap.org/#/pools

[4] https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/epr/03v09n3/0309flem/0309flem.html

[5] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/on-the-runtreasuries.asp

[6] https://clay.mirror.xyz/DwJ60O0R1IyRiPAZFBw4L05L3fd8PPxWnzDNedKtOas

[7] https://spinditty.com/industry/why-so-many-artists-hate-spotify

[8] https://spinditty.com/industry/why-so-many-artists-hate-spotify

Thank you to Brandon Carl, Nico Chinot, Clay Robbins, Maryam Mahdaviani, Aaron Frank, Iman Bright, and Charley Ma for reading and editing this in draft form.

To get notified when I publish a new essay, please subscribe here.