API Routing Layers in financial services

May 2020

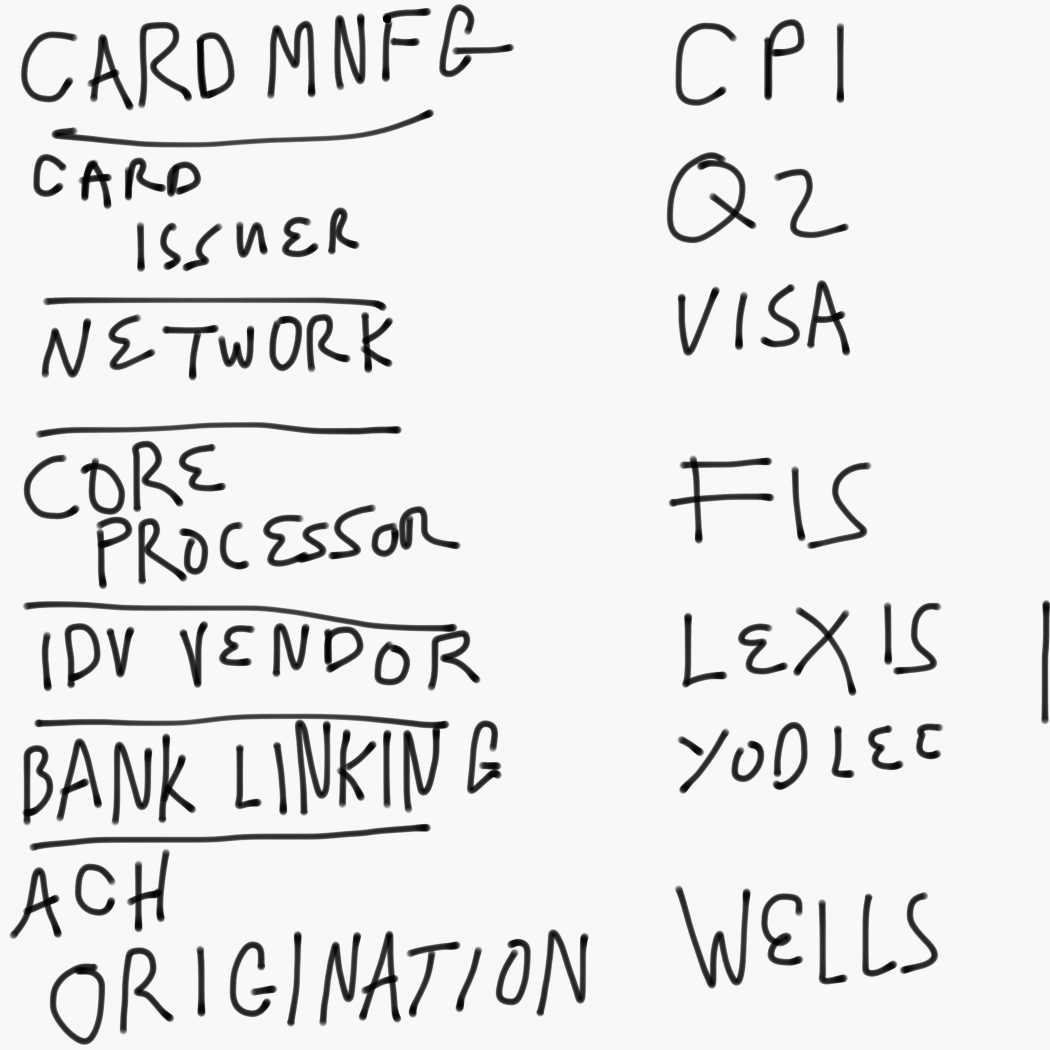

Every end customer facing financial services product is built on a stack of vendors. These vendors (roughly speaking) do things that the product team can’t (and shouldn’t) build themselves. For a typical neobank, here’s what that stack might look like:

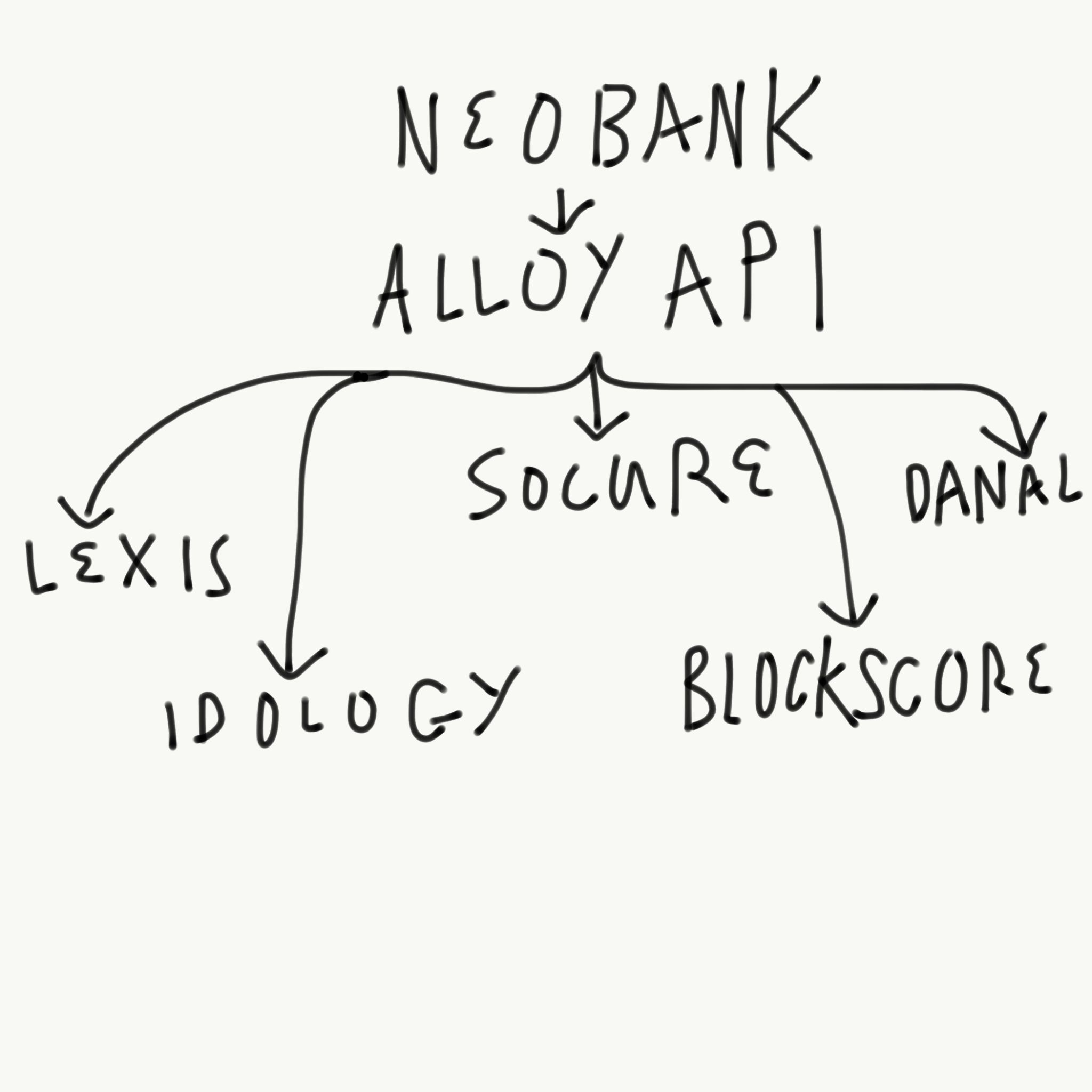

For each of these functions, there are typically several competing vendors. Sometimes the content is the same (Eg Idemia vs. CPI both manufacture cards) and sometimes the function is the same with different content (eg Q2 vs. Galileo both provide system of record/issuing processing services, but on top of different banks). An emergent strategy I’ve observed over the last several months is modern, developer driven companies aggregating all the vendors in competition, and serving them up to developers/fintech customers in a single API. Some examples of this are Alloy (aggregating several identity verification vendors and enabling you to access them from a single API) and Payitoff (aggregating several student loan programs and enabling you to access them all from a single API).

Macro trends behind this

Enterprise orgs for developer problems

Many fintech vendors are enterprise sales companies. Often, vendors of a similar service will differ in quality in subtle ways. The differences are typically too hard to detect in advance from a website or a reference call. For example, an IDV vendor might have terrible coverage of consumer identities in your specific demographic. Worse yet, if you’re a fast growing product, your use case and demographic will probably change quickly as you grow, and in some cases you’ll outgrow that vendor really quickly. This dynamic means that by the time you realize a vendor doesn't work for you, you've signed a contract and done an integration that you're now maintaining

Routing layers enable you to compare service quality and quickly switch vendors, without having to go through multiple enterprise sales cycles.

Bespoke Integrations & Implementations

Depending on where you are in the stack, these vendors can be quite complicated. A brand new issuer integration with a card manufacturer & personalization house, even when all parties are extremely motivated, takes multiple months with multiple people at each company, and there are myriad, subtle ways the integration can fail. I’ve heard of card personalization integrations where the cards shipped to customers with improperly encoded expiration dates and CVVs in the chip, so card swipes worked but dips and taps failed. These mistakes get even more expensive when you're scaling rapidly and you take on multiple integrations in sequence.

Routing layers enable you to get the technical benefits of multiple integrations with the execution burden of only one.

Organizational Distortion

5 years ago, barely any API routing layers in financial services existed (I can’t think of a single one). For a lot of these functions, fast growing financial services companies would shoulder the execution burden of building and maintaining multiple integrations on first generation APIs that had barely seen hypergrowth (a lot had seen large scale, growing rapidly from small to large, exposes many bugs that aren’t present when you’re steadily small or steadily large) . These services were rarely central to the core business, so they always eventually faced the awkward organizational decision of who owned it; who would keep the integration up to date, take the vendor calls, troubleshoot breaking issues, or renegotiate costs. Expertise would be hard to maintain because ambitious teams inside the company want to work on the main thing or the hot thing, not the necessary but non-core thing.

Routing layers solve this problem explicitly; they attach a revenue model to a (often unsexy) function, which funds its continued development and maintenance. For the fintech building on a routing layer, you might pay a slightly higher per unit price to consume the service (because the routing layer marks up the cost of the underlying vendor) but the overall organizational cost is lower, simply because you don’t have to distort your org by taking on non-core work.

In addition, many of these vendors will have embedded fixed costs such as implementation fees, monthly minimums, access fees, or support charges. Routing layers aggregate all these costs and amortize them across several customers. They might pass it on to a fintech in the form of higher unit costs, but for a pre-product market fit company, higher variable costs provide more flexibility than lower fixed costs.

A good example of the organization distortion effect is Stripe’s effect on acquiring. The emergence of Stripe unleashed hundreds of engineers at many companies who would otherwise be working on payments, to work on other parts of the business, because Stripe took out a lot of the overhead, and you no longer needed a payments team.

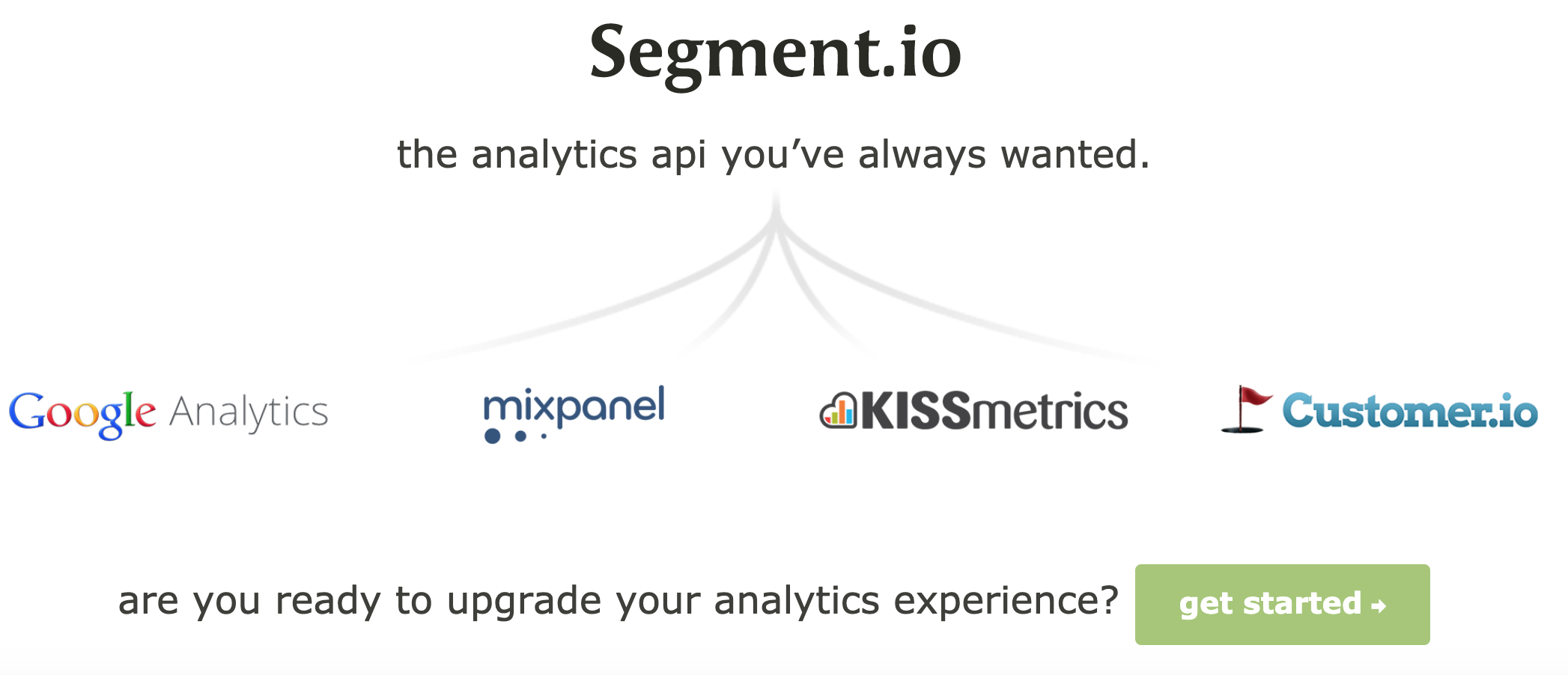

Segment for X

Segment was the first API routing layer I remember seeing. At launch, their value proposition was that you could call their APIs from your product, and get access to your analytics data in any analytics service, starting with Mixpanel, Google Analytics and Kissmetrics. The advantage was that you could easily switch between analytics services without having to re-instrument your product and without having to implement a new API.

One API, multiple vendors

The common thread amongst API routing layers I’ve seen is that they enable a single integration, that allows you to programmatically access multiple vendors without having to do an additional integration. Alloy for instance enables fintechs to access multiple identity verification vendors simply by integrating into Alloy’s APIs. This means you can integrate with Alloy and have peace of mind that you could access Lexis, Idology, Blockscore and others by just changing a parameter in the API request.

Advantages for early stage product teams

When done well, an API routing layer gives an early stage product team material advantages. First, they can access the breadth of functionality that would otherwise only be available to companies with a lot of resources. Second, an API routing layer gives you routing optionality; if a particular vendor is slow, expensive, unreliable, unsuitable, or down, you can switch to a competitor with minimal technical overhead. Third, lots of vendors are better than their competitors at subtle things. Using an API routing layer enables you to use the best vendor for the best job. An aggregator for card personalization would enable you to issue cards close to a cardholder’s location for faster delivery. An aggregator for acquiring merchant payments would enable you to smartly route payment traffic according to the needs of your customers - you can route between Stripe and Adyen because one is cheaper for a specific transaction type, has better acceptance for a particular set of transaction parameters, or is available in a country that the other is not.

Essentially, API routing layers enable fast growing products to quickly achieve the right cost, speed, reliability, or experience optimization for your business.

Tilting the field

The net result of API routing layers emerging in fintech is that small startups can, early in their development, have massive optionality and coverage, which enables similar impact and feature depth as large, well resourced incumbents. Large incumbents (or even in many cases later stage startups) had an advantage years ago because they invested in multiple integrations which gave them all the necessary optionality (primarily to reduce costs) and coverage (primarily to improve customer reach). API routing layers take away this advantage, because a startup can simply integrate once and get the same optionality, while the incumbent struggles to staff and maintain the legacy implementation. Of course, incumbents can integrate into API routing layers as well, but now they have an organizational problem; they have to assign a team to a non-core project, which already has its baggage, and that team has to swap out implementations in flight without breaking the customer experience, or trodding over the egos of internal stakeholders in the process.

There’s already a few examples of API routing layers in financial services, and there are a handful of parts of the ecosystem I’ve yet to see rolled up this way. Some examples of companies aggregating multiple APIs into one include:

Identity Verification:

- Aggregated vendors: Idology, Transunion, Lexis Nexis, Socure. Advantages:

- Easily switch between KYC vendors

- Reduce costs through switching

- Increasing pass rates by running customers through multiple vendors

- Companies: Alloy

Payroll linking & income verification

- Aggregated Services: ADP, Gusto, Paylocity, Gusto, Trinet, Paychex, Paycor. Advantages:

- Single lightweight integration

- Coverage of as many payroll providers as possible (and consequently enabling a user to access all their sources of income)

- Companies: Pinwheel, Atomic, Argyle

Student loan programs

- Federal, state, local, servicer specific, demography specific, economic status specific programs. Advantages

- Coverage of the widest range of programs for the widest range of students

- Minimal integration cost

- Companies: Payitoff, Summer

In full transparency, I'm invested in Payitoff, Alloy and Pinwheel.

Areas where this model may be applied

This model has been deployed frequently in SAAS and more recently in financial services, but I don't believe it's bounded to those domains. When looking at where else to apply it, it appears to be most effective in domains where there are lots of vendors providing functionally the same service, but they either a) cover different populations of end users, b) have a high degree of variability in the quality of their services, or c) are difficult to evaluate in advance before using them. Some financial services subdomains with no routing layers include:

Card manufacturing

- Idemia, CPI, G&D, Perfect Plastic, Arroweye

- Advantages: faster card delivery, redundancy

Merchant payment processing

- Stripe, Adyen, Braintree, Worldpay, Globalpayments, Bolt

- Advantages: cost, acceptance, redundancy

Credit checks for loan underwriting

- Vendors: Experian, Transunion, Equifax

- Advantages: cost, coverage

Bank account linking

- Plaid, Yodlee, Quovo, Finicity

- Advantages: Coverage, reliability

Bank account issuing

- Every BAAS platform: Q2, Marqeta, Synapse, Galileo, i2c,

- Advantages: Issuing cost, Reliability

Bank underwriting

- Radius, Evolve, Regions, Sutton

- Advantages: bank account portability

Outside of financial services, there are a few gargantuan domains, such as healthcare, construction, logistics, natural resources, and others that have a high degree of fragmentation and variability between legacy vendors. I suspect they would all benefit from this approach.

Thanks to Dami Omojola, Laura Spiekerman, Dhanji Prasanna, Justin Overdorff and Kurt Lin for reading this in draft form.

To get notified when I publish a new essay, please subscribe here.