Exploring the Transparency in Coverage final rule

I arrived in fintech post Dodd-Frank and in the middle of the Durbin Amendment playing out. All in all, the Durbin amendment aimed to reduce transaction costs in commerce, and had lots of unintended consequences as I’ve written about here, including (in my opinion) enabling the development of the fintech ecosystem as it exists today, by taking a fee pool that had formerly been accessible only to incumbents, and enabling upstarts like Cash App, Chime and Venmo to participate in it, and in so doing, funding the next generation of fintech infra like Marqeta.

Watching this play out, and more generally observing some of the ways we’ve had to react to legislative or regulatory enforcement changes in fintech at Cash App and in healthcare at Carbon Health, it’s clear that legislative changes, and the regulatory implementations of those legislations, often create openings for new businesses to be built in their wake.

In healthcare, there are 2 regulatory changes that are playing out right now, that I’m deeply interested in. The first is the Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangement (ICHRA). Among other things, ICHRA eliminates the tax advantaged status of employer funded insurance, by enabling employees to buy health plans on an exchange, using pre-tax dollars. I think this has the potential to accelerate the decoupling of employment and insurance in the US, increasing privacy and employee mobility in the US, and unwind almost 100 years of healthcare system design kicked off by WW2.

The second regulatory change (and the point of this essay) is the Transparency in Coverage final rule. This went into effect on July 1, 2022, and it forces insurers to publish the contract rates they have negotiated with every healthcare provider in network in that plan, for every service covered by that plan, the out of network rates of that plan, the specific clinicians (by NPI) covered in the plan, in a standard machine readable format (seems they learned their lesson from the hospital price transparency rule where hospitals simply published a bunch of garbage thereby continuing to obfuscate pricing). It does a lot of other things too.

These price transparency rules are going into effect at a time when rising healthcare costs (which basically always rise) are increasingly being borne by consumers (either through high deductible plans, exchange buyers or more people than ever becoming 1099 workers). At the same time, consumers have long lacked a way to price-compare when choosing medical services, and employers have long lacked visibility into the relative costs of the clinical choices their employees could make. Together the rules create a foundation to provide price transparency to healthcare buyers (whether you’re a consumer picking a specific service, or you’re an employer choosing providers to be in-network) that did not exist before.

How it works

Each month, every self insured [2] employer (typically facilitated by TPAs like United, Aetna, etc) is required to publish an updated list of files that include their in network rates with every provider they’re contracted with, in a standard JSON format specified by CMS. A useful schema for the in network files is available here. These include

- (usually) A reference or index, that functions as a table of contents for where to look to find what plans you’re specifically looking for. For example, here is Anthem’s index / table of contents for December 2022. It’s 30GB: Table of Contents. United on the other hand, hosts all ~50k plans here on the web. I’d say the index is the least consistent thing I’ve encountered so far while exploring.

- In-network rates [3]: files containing

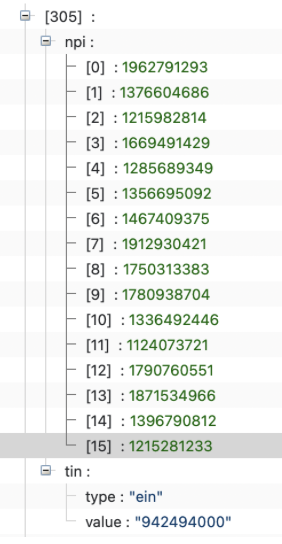

- a list or provider groups (organized by Tax Identification Number, or TIN), providers (organized by NPI). Providers are often credentialed under multiple provider groups. Here’s what one looks like (for one of the Aetna Health of California Fully Insured plans)

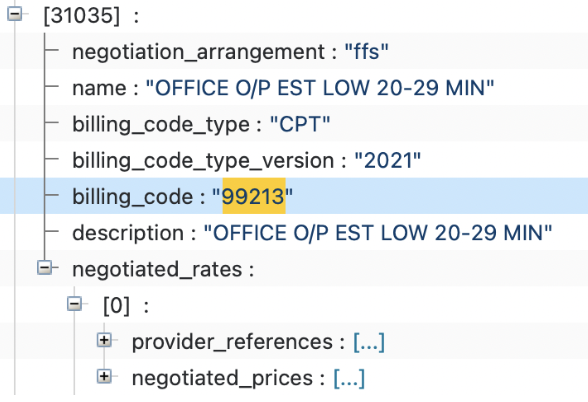

- and the negotiated rates (usually organized by CPT code from what I’ve seen, but other billing code types are accepted, see here) that the payor has with those provider groups who are in network with the plan. For example for the routine office visit CPT code (99213) here’s what the same Aetna plan looks like

Tools for exploring the data

Over the course of the last few weeks I’ve used several tools to get access to the data, compare it, and generally make sense of it all

- Dadroit: desktop tool for processing large JSON files.There’s a free version so you can get pretty far with it if you’re patient

- Dolthub: they’re running a bounty program for some healthcare providers to process the machine readable files, and have some useful code snippets in case you’re a little bit technical

- ChatGPT: I know it sounds weird, but this helped adapt some simple python scripts when I got stuck

- Cascade Health[4]: if you’re doing this at scale, they can help you

- HealthPlanExplorer: I built this with some collaborators over the last couple of weeks to help process the files more quickly into formats useful for me. Costs a bit to pay for the box. If you have feedback, I’d love to hear it.

Questions and Problems

A few things have stuck out that, at first, will limit how impactful this data can be and how widely it can be used.

The files are too large to be usable

The consistent file structures really help, but most of the in network files are huge (I’ve seen in-network files ranging in size from 800MB to 600GB). These sizes are simply impractical to interact with unless you’re fairly technical (and as it stands, there aren’t simple online tools that make it easy to spelunk through this data), and as a result, most healthcare providers will simply not bother until tools for using these are widespread and cheap. The other dynamic here is that even though CMS recommends that insurers keep historical copies of their in-network rates, basically no insurers are keeping historical files accessible (most just keep the current period’s files). I suspect this is because hosting and bandwidth on these files is probably insanely expensive at these scales. So if you want to run a time series on a specific insurer, healthcare provider, or both, and understand how pricing is changing, you have to save the files yourself.

There’s too many of them:

Pricing is made available at a plan level rather than a payor level. This advantages anyone doing analysis that indexes on a specific employer. But if you’re not looking at the level of a specific provider, there are 2 disadvantages:

- In my experience, when insurers negotiate contracts with healthcare providers, they often negotiate across a class of plans (eg all Aetna commercial plans) rather than at a specific plan level. From what I’ve seen at Carbon, our contracts typically apply across a class of plans rather than a specific plan).This means that there’s probably significant rate duplication across plans as presented in the disclosed files (ie the Aetna Google Plans and the Aetna Netflix plans are unlikely to have different negotiated rates with a random cardiologists practice. But each plan is available to you to look at as a 90GB file).

- It’s rare that consumers know their actual detailed plan. A Netflix employee probably just knows that they are on a Netflix Anthem plan, not that they’re on the Netflix Anthem Silver 1500 California plan.

Provider lists are incomplete

My read so far looking through the in-network files is that there’s some rate of error thats difficult to quantify from a provider perspective. For example, I’ve seen commercial plans with specific payors that I know we’re in network with, but I’m unable to find our provider groups and providers represented in the in-network files. I’m personally relatively new to this domain, but after looking at several dozen plans I have a high suspicion that a lot of the data is simply incomplete (as in the insurers have omitted lots of providers who are actually in network, whether intentionally or not) and they all know that there’s just so many files and the files are so large, that it’s unlikely they’ll ever get caught or penalized for it.

The rates are . . . wrong?

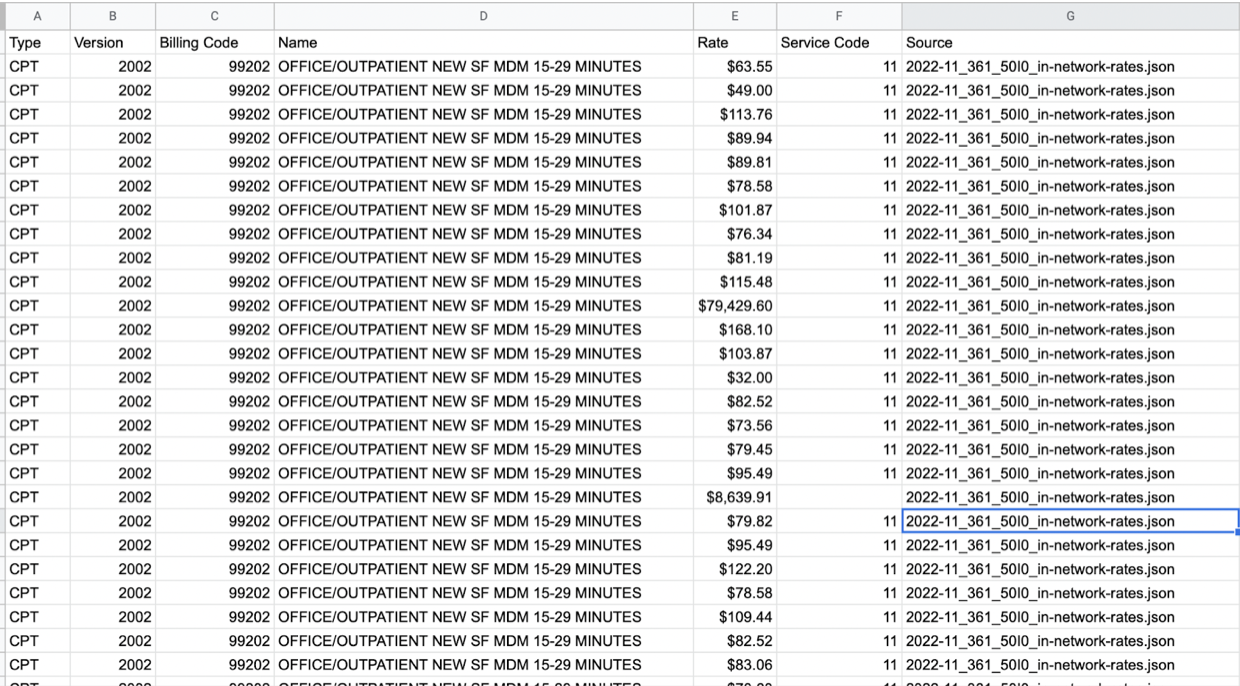

Will report back on this later. Given how large the surface area is, I wouldn’t be surprised if lots of negotiated rates represented in these files are simply incorrect. When comparing publicly posted rates for a few payers with our internal contracted rates, I haven’t once been able to find a match. My current hypotheses right now are a) that there are some additional fees or multipliers not represented in our internal contracted rate tables (but potentially represented elsewhere in contracts), that are lumped into the public contract rates, and I’ve just not done enough digging, or b) the lack of precision is due to regional differences in rates for the same service, and because the transparency in coverage schemas don’t have a way to identify each contracted region, you just kinda can’t tell. To illustrate this, take a look at the in-network rates for CPT code 99202 (a fairly common office visit code) posted in the November 2022 machine readable files for a large national insurer in contract with Carbon, for all the Netflix plans. For Netflix, this insurer has

- 68 different negotiated rates for 99202

- Ranging from $0 to $80k! For the service

- With no way to discern the reason the prices differ between the services (hence my theories above)

There’s no directory

There’s no central source that tells you where to go for all these files. Even each insurer has bespoke directories. United Health Care stores all files in a single location on it’s site. Aetna does not maintain a directory for self insured employer plans (for example Adobe has several plans administered by Aetna hosted here, but you can only navigate to it from a Google search, and you can’t access it from Aetna’s own directory here). This is almost certainly intentional.

My current read is that if you want to spelunk through these data, you need to be fairly technical and know exactly what you’re looking for. Otherwise you’ll spend countless hours like I have and most likely won’t make sense of it. In addition, it’s simply so much data that there aren’t consumer solutions for storing it all (I think this is even true at SMB scale - it’s like a petabyte of data a month, and much of it is probably dupes). As a result I think a crop of companies (like Cascade Health [4]) will emerge to help make sense of the data and enable employers, consumers and providers utilize it.

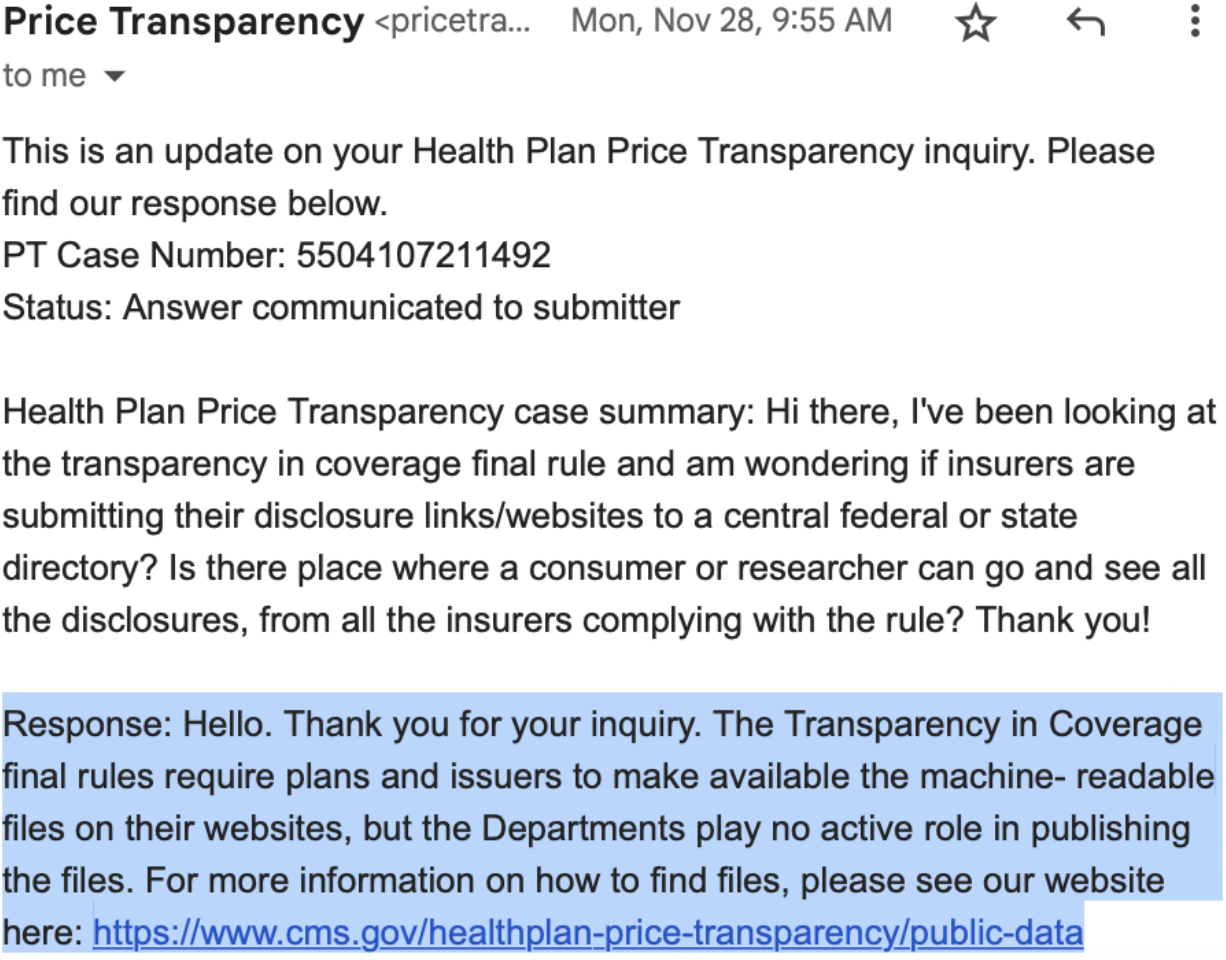

Policy Based Improvements

As these rules & space evolve, two things I think the teams at CMS implementing them should consider. First, a central repository or directory where each payor lists their machine readable files. This will simultaneously reduce the cost of enforcement by ensuring that all payors are complying, making it easy to tell which payors are complying and submitting data and which are not, whether they’re up to date, and making it easy to verify that the data is complete. I asked about this a while back and it looks like it’s not currently in the plans, but without it, enforcement of these rules will be through costly, slow, court-based processes like the self funded plans currently suing Anthem[1].

Lower cost enforcement means more plans will comply, and a directory means data will be cheaper and easier to compare, which will lead to more data being shared, and that data being more accurate.

The second improvement is to add a geographic parameter (either in state or ZIP) to the in-network rates so its possible to work backwards to which regions specific rates apply to. If you’re looking at the rates for a small, single location provider, then you can assume that the rates apply specifically in that location. If you’re looking at the in-network rates for a provider in multiple markets, it is difficult to tell which rates apply to which market. There are some workarounds for this (for example, you can look at the NPIs covered in a particular rate agreement, and work backwards from where that provider practices) but they are all probabilistic because very often the NPI registry is delayed, or that particular provider is licensed in multiple stats. I don’t believe payors will voluntarily do this, so the only way to extract this insight is by adjusting the policy or requirement.

Pretty excited about these possibilities and what they mean for patient access. If you’re working on this I’d love to chat! Will share more as I learn more, and the next essay will about the most impactful use cases I've encountered so far.

[3] Files containing Out-of-network rates for each plan are also included, but that unlocks totally separate use cases that I’ll try to cover in another essay.

[4] In full disclosure, I’m an investor in Cascade Health.

Thank you to Ana-Maria Constantin for reading and editing this in draft form

To get notified when I publish a new essay, please subscribe here.